* Noise and Ray Marching

[[https://literatelb.org][LiterateLB's]] volumetric visualization functionality relies on a simple ray marching implementation

to sample both the 3D textures produced by the simulation side of things and the signed distance

functions that describe the obstacle geometry. While this produces surprisingly [[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n86GfhhL7sA][nice looking]]

results in many cases, some artifacts of the visualization algorithm are visible depending on the

viewport and sample values. Extending the ray marching code to utilize a noise function is

one possibility of mitigating such issues that I want to explore in this article.

While my [[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2al5tV14M8][original foray]] into just in time visualization of Lattice Boltzmann based simulations

was only an aftertought to [[https://tree.kummerlaender.eu/projects/symlbm_playground/][playing around]] with [[https://sympy.org][SymPy]] based code generation approaches I have

since put some work into a more fully fledged code. The resulting [[https://literatelb.org][LiterateLB]] code combines

symbolic generation of optimized CUDA kernels and functionality for just in time fluid flow

visualization into a single /literate/ [[http://code.kummerlaender.eu/LiterateLB/tree/lbm.org][document]].

For all fortunate users of the [[https://nixos.org][Nix]] package manager, tangling and building this from the [[https://orgmode.org][Org]]

document is as easy as executing the following commands on a CUDA-enabled NixOS host.

#+BEGIN_SRC sh

git clone https://code.kummerlaender.eu/LiterateLB

nix-build

./result/bin/nozzle

#+END_SRC

** Image Synthesis

The basic ingredient for producing volumetric images from CFD simulation data is to compute

some scalar field of samples \(s : \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}_0^+\). Each sample \(s(x)\) can be assigned a color

\(c(x)\) by some convenient color palette mapping scalar values to a tuple of red, green and blue

components.

[[https://literatelb.org/tangle/asset/palette/4wave_ROTB.png]]

The task of producing an image then consists to sampling the color field along a ray assigned

to a pixel by e.g. a simple pinhole camera projection. For this purpose a simple discrete

approximation of the volume rendering equation with constant step size \(\Delta x \in \mathbb{R}^+\) already

produces suprisingly good pictures. Specifically

$$C(r) = \sum_{i=0}^N c(i \Delta x) \mu (i \Delta x) \prod_{j=0}^{i-1} \left(1 - \mu(j\Delta x)\right)$$

is the color along ray \(r\) of length \(N\Delta x\) with local absorption values \(\mu(x)\). This

local absorption value may be chosen seperately of the sampling function adding an

additional tweaking point.

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

#+END_EXPORT

The basic approach may also be extended arbitrarily, e.g. it is only the inclusion of a couple

of phase functions away from being able [[https://tree.kummerlaender.eu/projects/firmament/][recover the color produced by light travelling through the participating media that is our atmosphere]].

** The Problem

There are many different possibilities for the choice of sampling function \(s(x)\) given the results of a

fluid flow simulation. E.g. velocity and curl norms, the scalar product of ray direction and shear layer

normals or vortex identifiers such as the Q criterion

\[ Q = \|\Omega\|^2 - \|S\|^2 > 0 \text{ commonly thresholded to recover isosurfaces} \]

that contrasts the local vorticity and strain rate norms. The strain rate tensor \(S\) is easily

recovered from the non-equilibrium populations \(f^\text{neq}\) of the simulation lattice — and is in

fact already used for the turbulence model. Similarly, the vorticity \(\Omega = \nabla \times u\) can be

computed from the velocity field using a finite difference stencil.

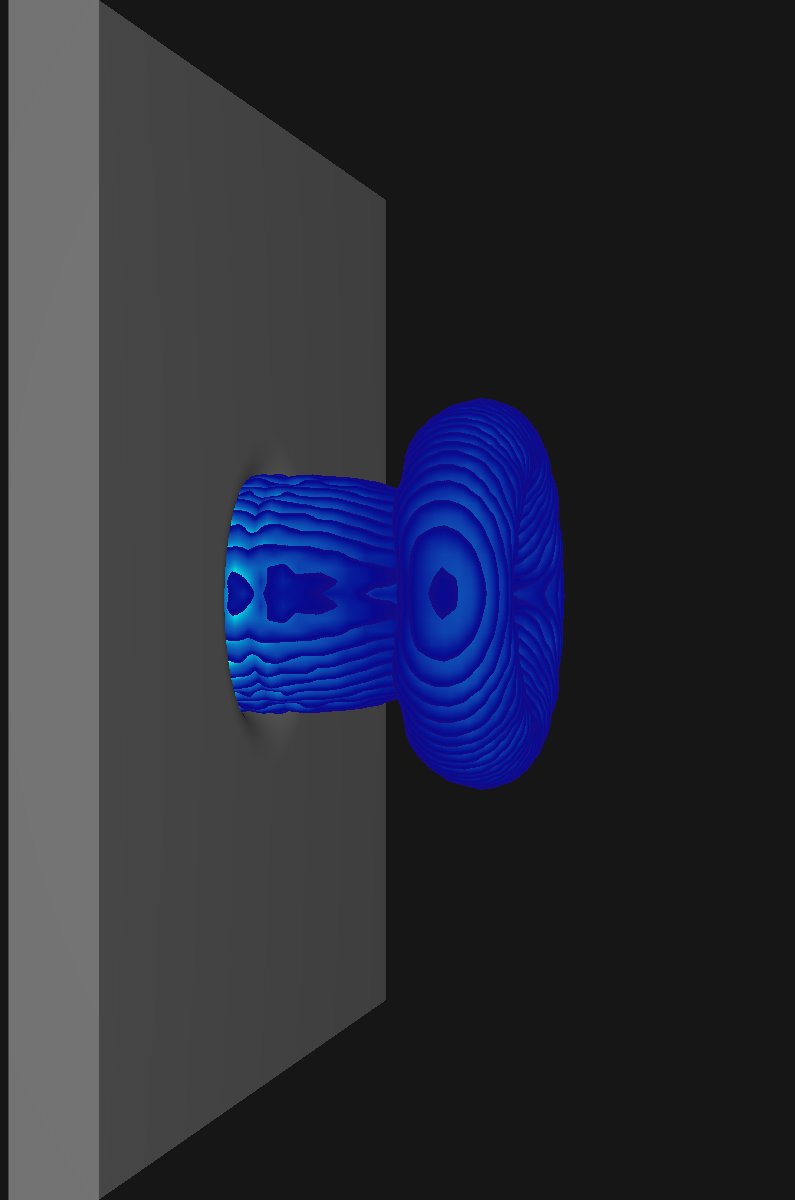

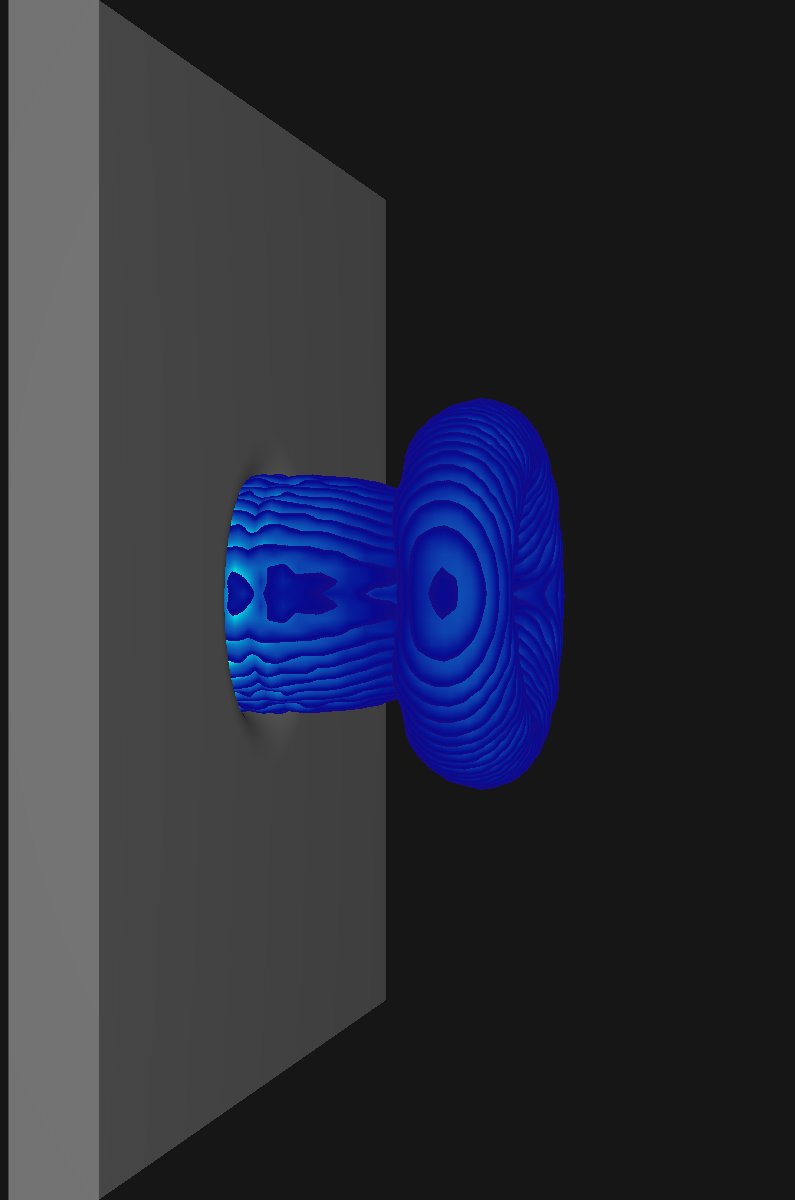

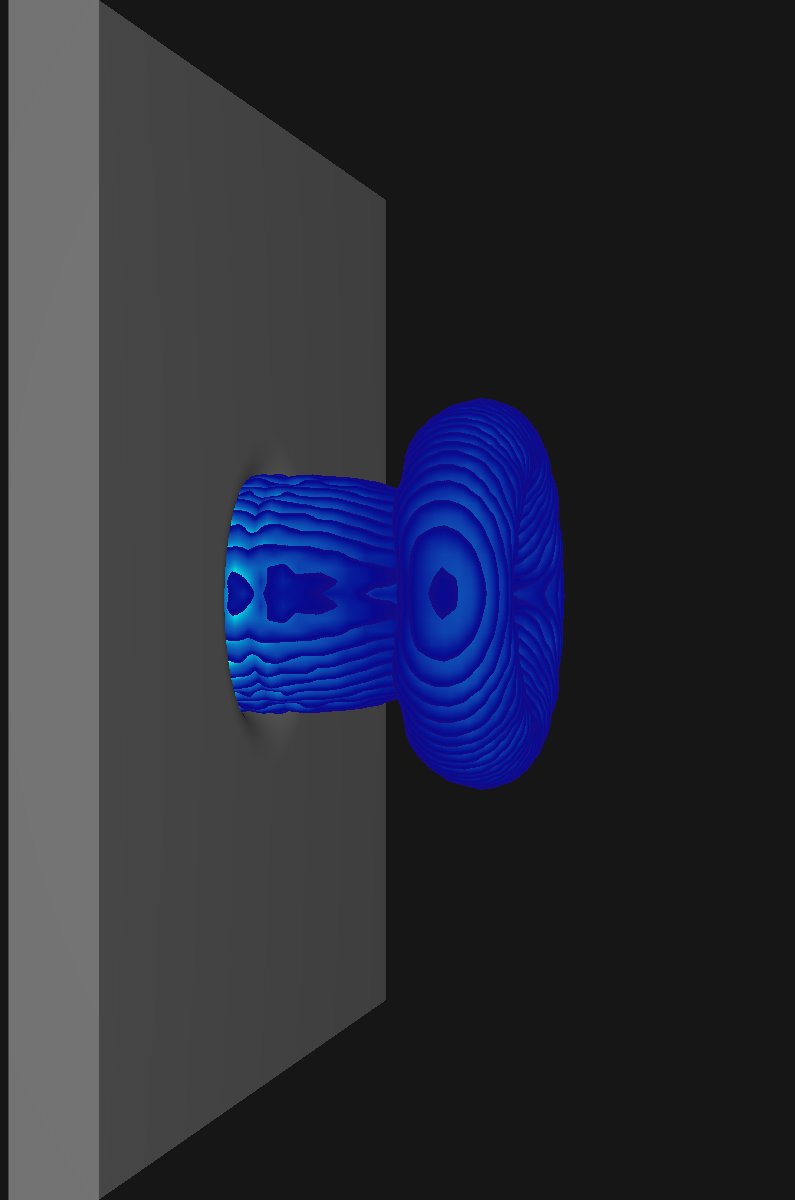

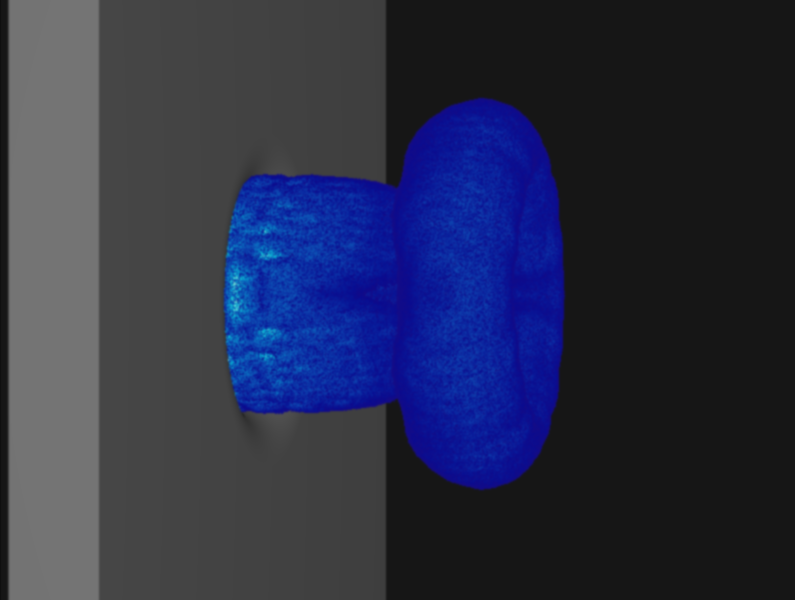

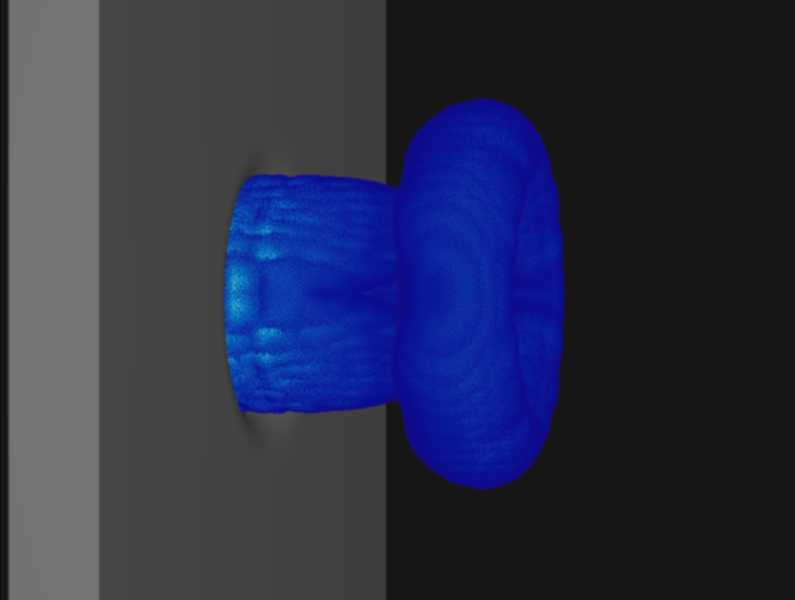

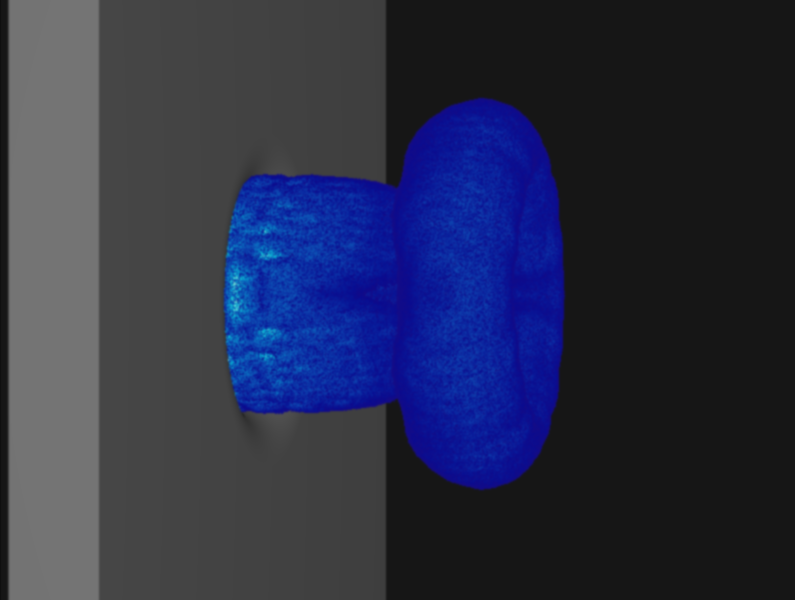

The problem w.r.t. rendering when thresholding sampling values to highlight structures in the flow

becomes apparent in the following picture:

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

Q Criterion

Curl Norm

#+END_EXPORT

While the exact same volume discretization was used for both visualizations, the slices are much

less apparent for the curl norm samples due to the more gradual changes. In general the issue is

most prominent for scalar fields with large gradients (specifically the sudden jumps that occur

when restricting sampling to certain value ranges as is the case for the Q criterion).

** Colors of Noise

The reason for these artifacts is primarily choice of start offsets w.r.t. the traversed volume

in addition the the step width. While this tends to become less noticable when decreasing said

steps, this is not desirable from a performance perspective.

What I settled on for LiterateLB's renderer are view-aligned slicing and random jittering to remove

most visible artifacts. The choice of /randomness/ for jittering the ray origin is critical here as plain

random numbers tend to produce a distracting static-like pattern. A common choice in practice is

to use so called /blue noise/ instead. While both kinds of noise eliminate most slicing artifacts, the

remaining patterns tend to be less noticeable for blue noise. Noise is called /blue/ if it contains only

higher frequency components which makes it harder for the pattern recognizer that we call brain to

find patterns where there should be none.

The [[https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/1913/0000/Void-and-cluster-method-for-dither-array-generation/10.1117/12.152707.short?SSO=1][void-and-cluster algorithm]][fn:vac] provides a straight forward method for

pre-computing tileable blue noise textures that can be reused during the actual visualization.

Tileability is a desirable property for this as we otherwise would either need a noise texture

large enough to cover the entire image or instead observe jumps at the boundary between

the tiled texture.

The first ingredient for /void-and-cluster/ is a =filteredPattern= function that applies a

plain Gaussian filter with given $\sigma$ to a cyclic 2d array. Using cyclic wrapping during the

application of this filter is what renders the generated texture tileable.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

def filteredPattern(pattern, sigma):

return gaussian_filter(pattern.astype(float), sigma=sigma, mode='wrap', truncate=np.max(pattern.shape))

#+END_SRC

This function will be used to compute the locations of the largest void and tightest

cluster in a binary pattern (i.e. a 2D array of 0s and 1s). In this context a /void/ describes

an area with only zeros and a /cluster/ describes an area with only ones.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

def largestVoidIndex(pattern, sigma):

return np.argmin(masked_array(filteredPattern(pattern, sigma), mask=pattern))

#+END_SRC

These two functions work by considering the given binary pattern as a float array that is blurred by

the Gaussian filter. The blurred pattern gives an implicit ordering of the /voidness/ of each pixel, the

minimum of which we can determine by a simple search. It is important to exclude the initial binary

pattern here as void-and-cluster depends on finding the largest areas where no pixel is set.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

def tightestClusterIndex(pattern, sigma):

return np.argmax(masked_array(filteredPattern(pattern, sigma), mask=np.logical_not(pattern)))

#+END_SRC

Computing the tightest cluster works in the same way with the exception of searching the largest array

element and masking by the inverted pattern.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

def initialPattern(shape, n_start, sigma):

initial_pattern = np.zeros(shape, dtype=np.bool)

initial_pattern.flat[0:n_start] = True

initial_pattern.flat = np.random.permutation(initial_pattern.flat)

cluster_idx, void_idx = -2, -1

while cluster_idx != void_idx:

cluster_idx = tightestClusterIndex(initial_pattern, sigma)

initial_pattern.flat[cluster_idx] = False

void_idx = largestVoidIndex(initial_pattern, sigma)

initial_pattern.flat[void_idx] = True

return initial_pattern

#+END_SRC

For the initial binary pattern we set =n_start= random locations to one and then repeatedly

break up the largest void by setting its center to one. This is also done for the tightest cluster

by setting its center to zero. We do this until the locations of the tightest cluster and largest

void overlap.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

def blueNoise(shape, sigma):

#+END_SRC

The actual algorithm utilizes these three helper functions in four steps:

1. Initial pattern generation

#+BEGIN_SRC python

n = np.prod(shape)

n_start = int(n / 10)

initial_pattern = initialPattern(shape, n_start, sigma)

noise = np.zeros(shape)

#+END_SRC

3. Eliminiation of =n_start= tightest clusters

#+BEGIN_SRC python

pattern = np.copy(initial_pattern)

for rank in range(n_start,-1,-1):

cluster_idx = tightestClusterIndex(pattern, sigma)

pattern.flat[cluster_idx] = False

noise.flat[cluster_idx] = rank

#+END_SRC

4. Elimination of =n/2-n_start= largest voids

#+BEGIN_SRC python

pattern = np.copy(initial_pattern)

for rank in range(n_start,int((n+1)/2)):

void_idx = largestVoidIndex(pattern, sigma)

pattern.flat[void_idx] = True

noise.flat[void_idx] = rank

#+END_SRC

5. Elimination of =n-n/2= tightest clusters of the inverted pattern

#+BEGIN_SRC python

for rank in range(int((n+1)/2),n):

cluster_idx = tightestClusterIndex(np.logical_not(pattern), sigma)

pattern.flat[cluster_idx] = True

noise.flat[cluster_idx] = rank

#+END_SRC

For each elimination the current =rank= is stored in the noise texture

producing a 2D arrangement of the integers from 0 to =n=. As the last

step the array is divided by =n-1= to yield a grayscale texture with values

in $[0,1]$.

#+BEGIN_SRC python

return noise / (n-1)

#+END_SRC

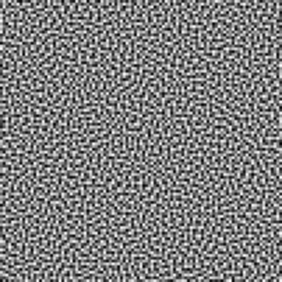

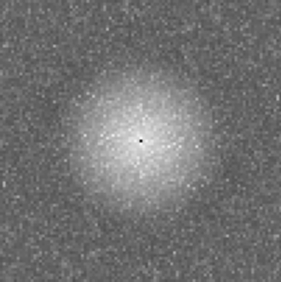

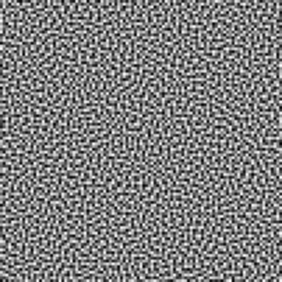

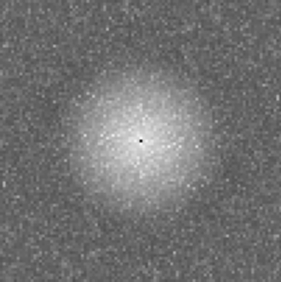

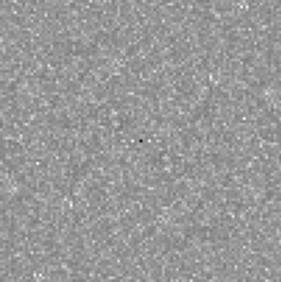

In order to check whether this actually generated blue noise, we can take a

look at the Fourier transformation for an exemplary \(100 \times 100\) texture:

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

Blue noise texture

Fourier transformation

#+END_EXPORT

One can see qualitatively that higher frequency components are significantly more

prominent than lower ones. Contrasting this to white noise generated using uniformly

distributed random numbers, no preference for any range of frequencies can be

observed:

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

White noise texture

Fourier transformation

#+END_EXPORT

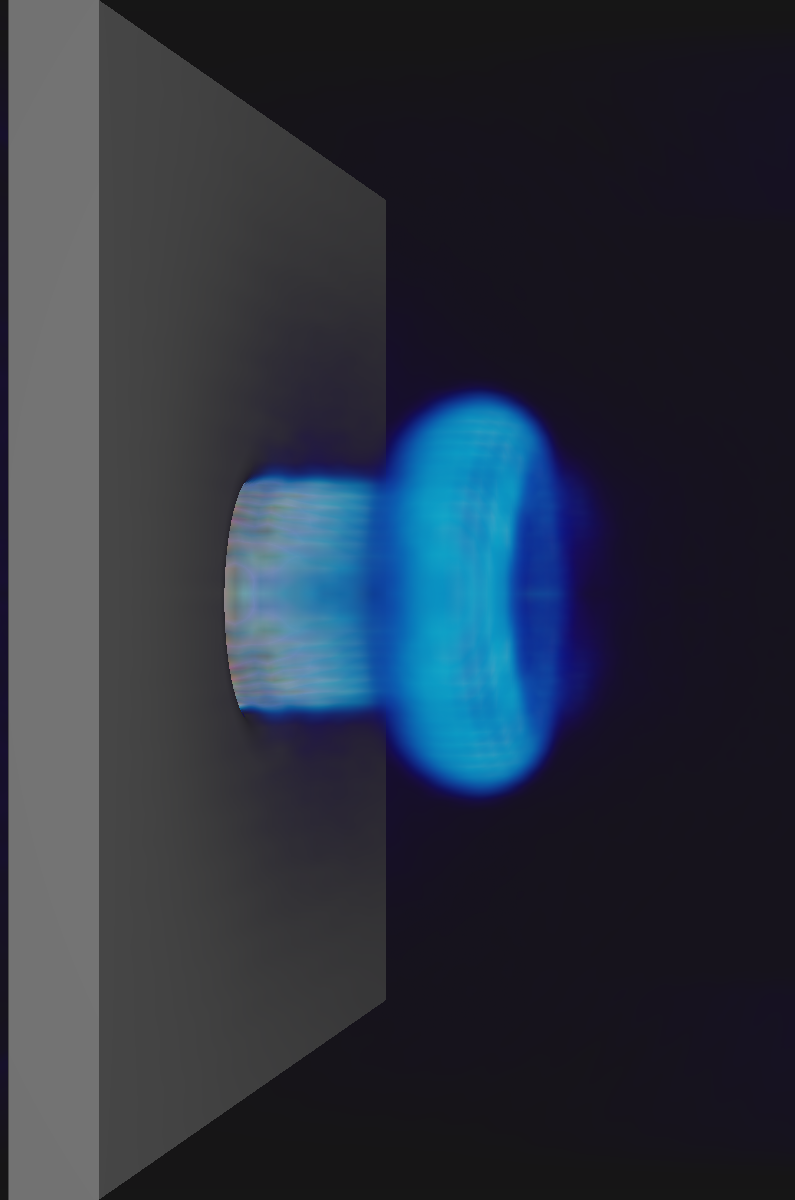

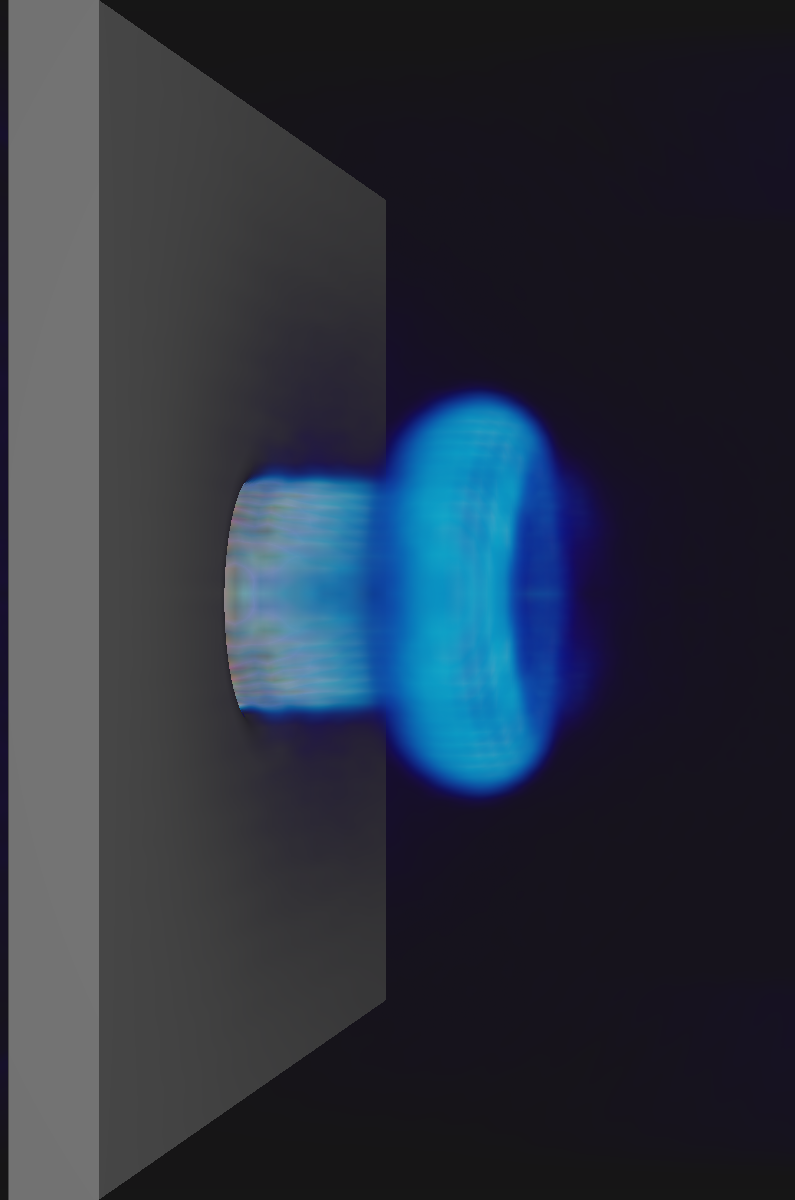

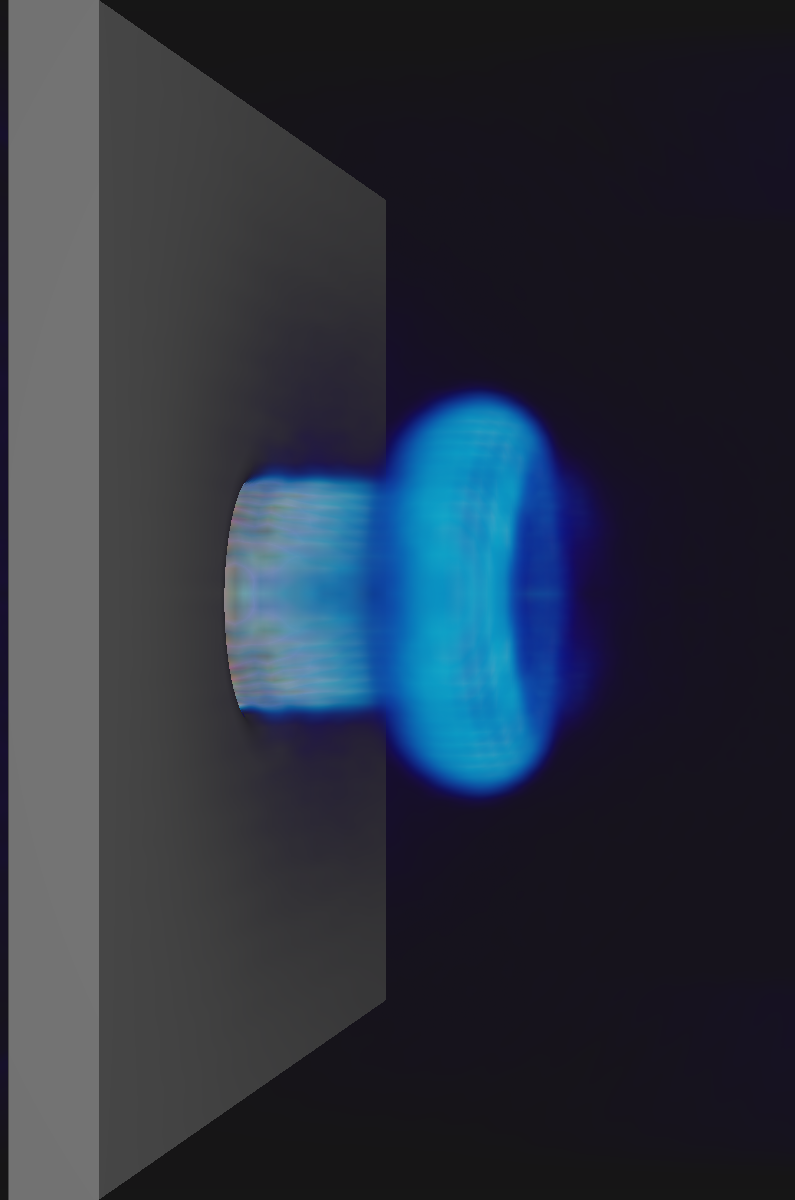

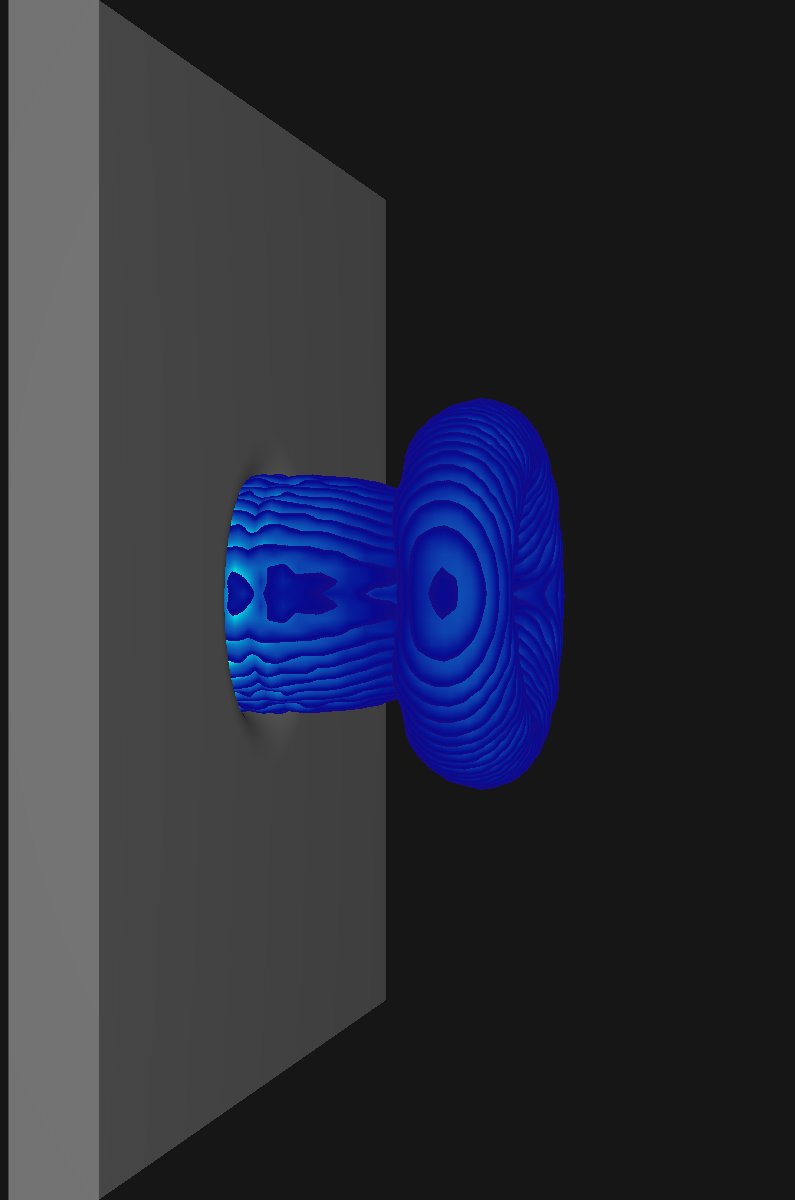

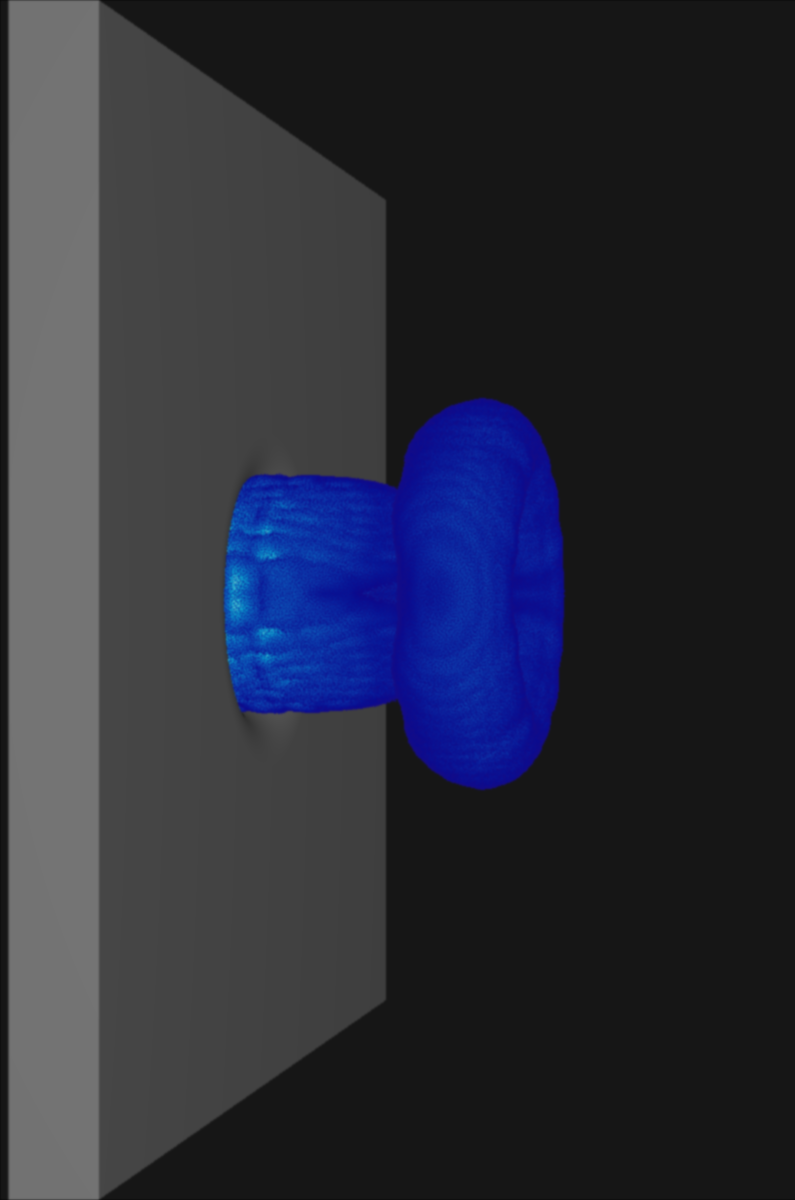

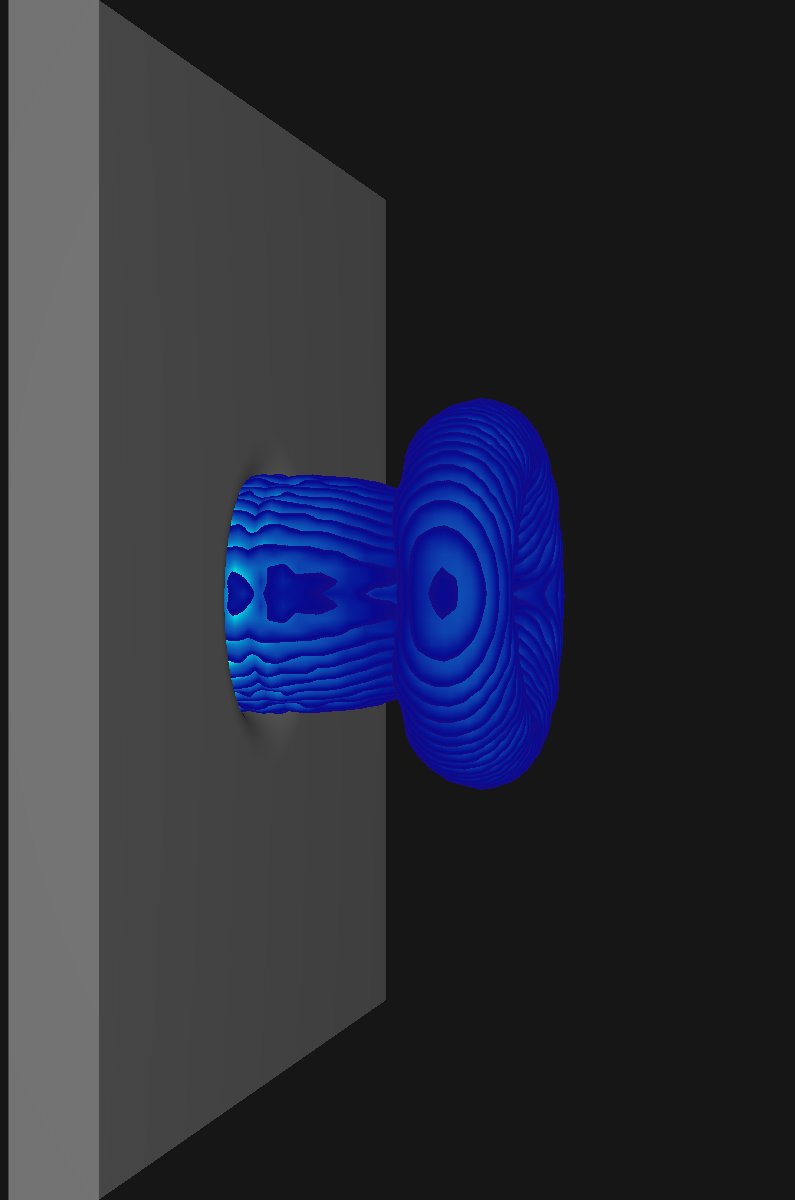

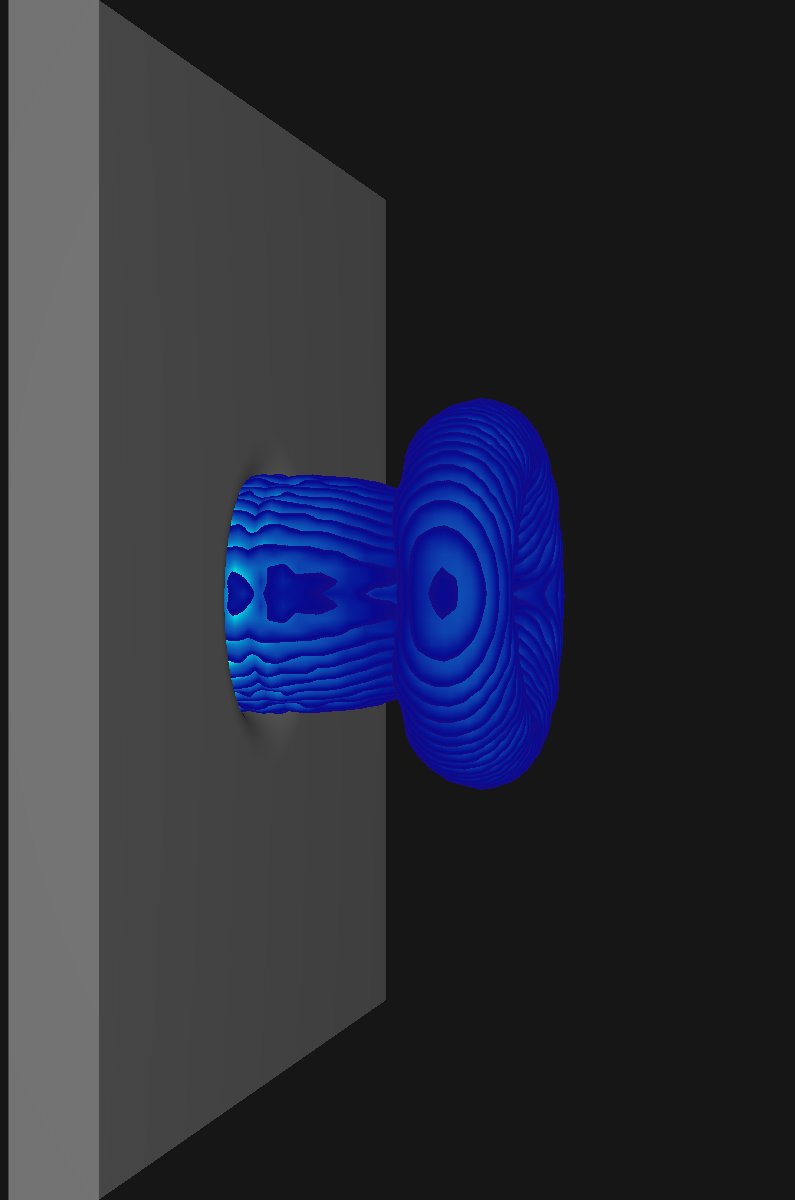

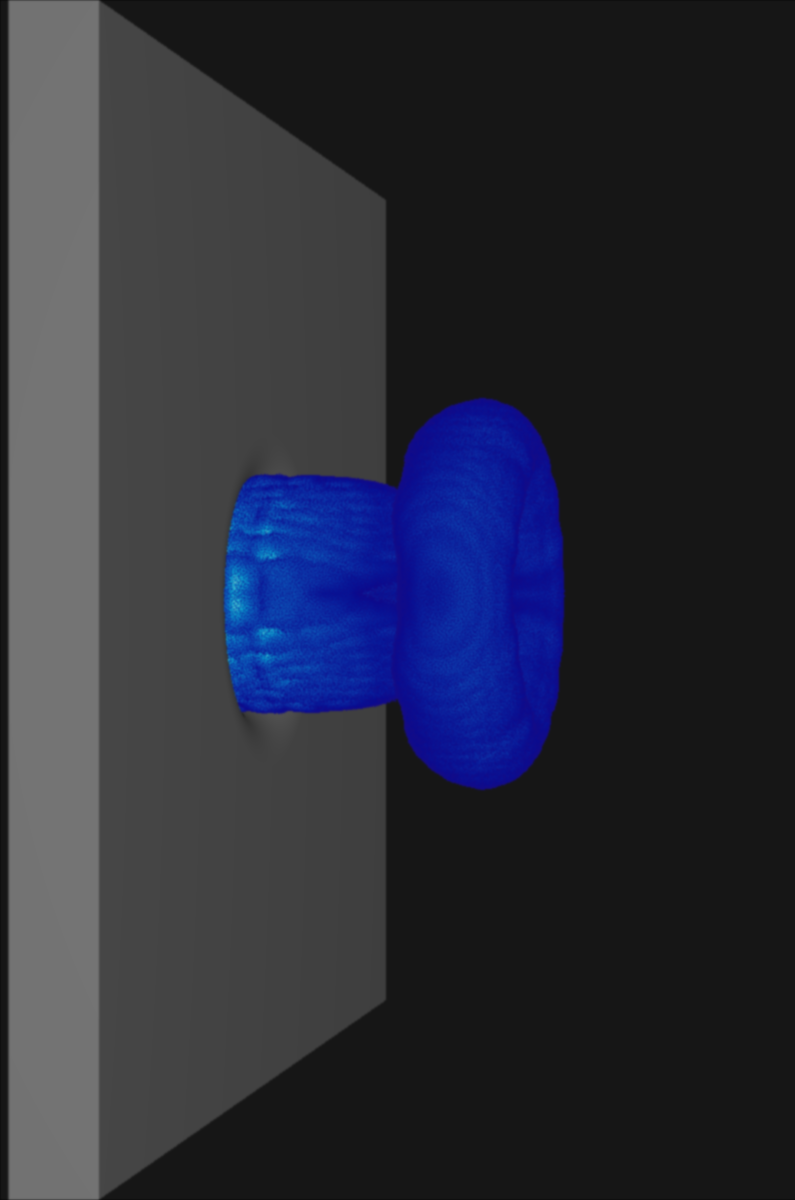

** Comparison

Contasting the original Q criterion visualization with one produced using blue noise jittering

followed by a soft blurring shader, we can see that the slicing artifacts largely vanish.

While the jittering is still visible to closer inspection, the result is significantly more pleasing

to the eye and arguably more faithful to the underlying scalar field.

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

Simple ray marching

Ray marching with blue noise jittering

#+END_EXPORT

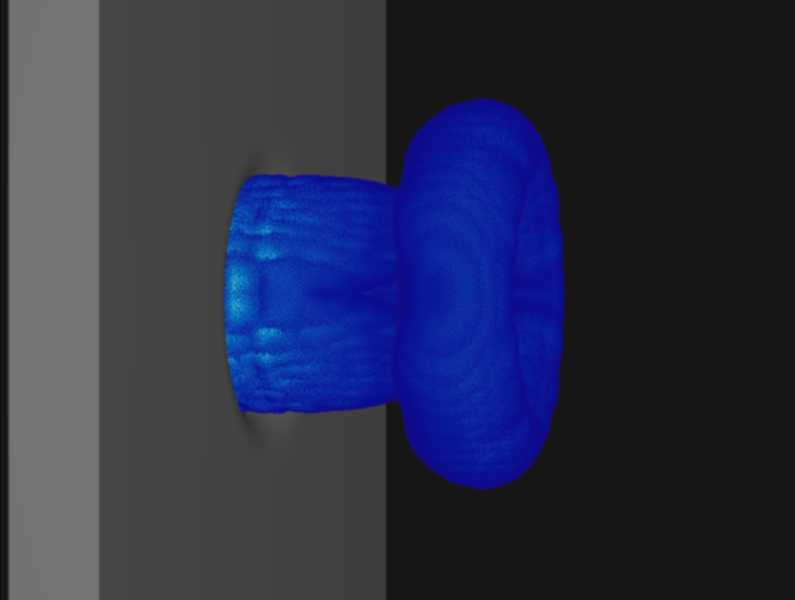

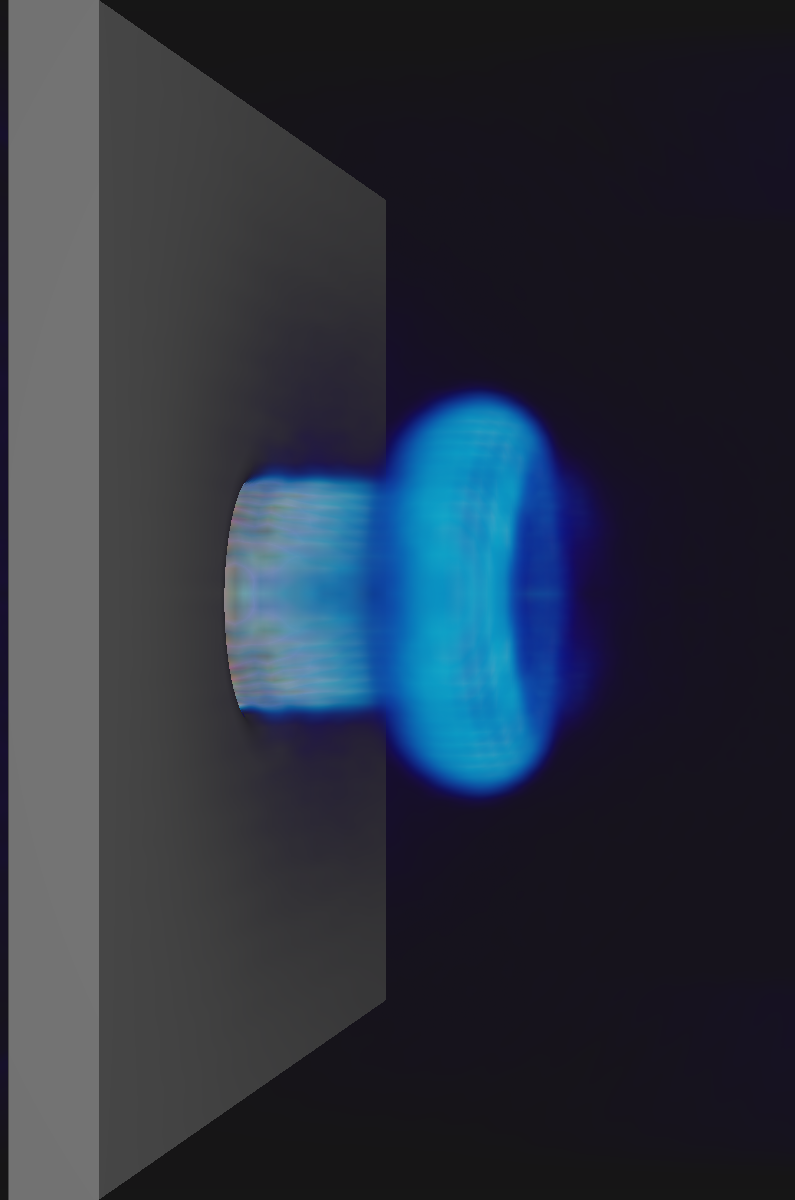

While white noise also obcures the slices, its lower frequency components

produce more obvious static in the resulting image compared to blue noise.

As both kinds of noise are precomputed we can freely choose the kind of

noise that will produce the best results for our sampling data.

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

Blue noise

White noise

#+END_EXPORT

In practice where the noise is applied just-in-time during the visualization of

a CFD simulation, all remaining artifacts tend to become invisible. This can

be seen in the following video of the Q criterion evaluated for a simulated

nozzle flow in LiterateLB:

#+BEGIN_EXPORT html

#+END_EXPORT

[fn:vac] Ulichney, R. Void-and-cluster method for dither array generation. In Electronic Imaging (1993). DOI: [[https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/1913/0000/Void-and-cluster-method-for-dither-array-generation/10.1117/12.152707.short?SSO=1][10.1117/12.152707]].